2011: “No one got in our way”: A Retrospective on the Pump Station 1 Leak and Shutdown

On a Saturday morning in early January 2011, a technician on rounds at Pump Station 1 discovered oil leaking in the Booster Pump Building. Alyeska launched a days-long response that would become historical in proportion. Ultimately, the TAPS team delivered an incredible outcome against the toughest of circumstances.

This oral history reconstructs the events, drawing on memories from some of those most central to the effort. At the time, they served in these roles:

- James “JB” Johnson, the Technician at Pump Station 1 who discovered the leak.

- Cathy Girard, an Environmental Coordinator on shift at PS1.

- John Baldridge, the Senior Pipeline Director, who served as Incident Commander for the Incident Management Team in Fairbanks.

- Brendan Labelle-Hamer, a Pump Station 1 supervisor, who was called in to lead night shift.

- Mike Malvick, an operations engineering supervisor, with unique knowledge about shutdowns in cold weather.

- Gerald “Jerry” Albro, a senior mechanical engineer, and Alyeska’s contingency response piping engineer, who lead the engineering work.

- Tom Barrett, Alyeska’s President, whose first day on the job was Jan. 1, 2011.

- Mike Hale, a Project Manager with welding experience, who was sent to PS1 for on-the-scene support.

- Betsy Haines, Oil Movements Department Director, who oversaw the Operations Control Center.

It was January 8, 2011, and at Pump Station 1, a discovery in the Booster Pump Building began a critical chapter in TAPS’ history.

JB: After shift-change, I was out doing my rounds, on the route I took every day. I got to the booster pump room, and I could smell the crude. I could smell it from the hallway. Crude vapors. I knew there was a leak. That building has a basement with grating above, so you could see through to the floor, and I saw oil coming in from the wall and pipe. I made an emergency call to all personnel: “We have a major leak. Bring a respirator before coming.” I went and got one, waited inside the hallway, and the supervisor and lead tech showed up and I took them in.

Cathy: It was in the morning and I was in my office at the pump station. I heard the radio call when JB Johnson said, “Control room, we have crude oil in the booster pump building.” I heard that, and it was dead silence on the radio. I listened. I was waiting. And eventually I ended up making it into the control room. I asked, “Is this for real?” Yeah, it was real. I called my supervisor Jim Lawler and let him know. He said, “Do you think you’ll need any help?” I said, “I think we’ll be OK.” Wrong answer. It got bigger.

John: I was at home. It was a Saturday morning and (Pump Station 1 Supervisor) Rick Larsen calls me up. He said, “Hey John, we’ve got a problem. We’ve got oil coming into the booster pump house basement.” I thought about that for a second and said, “Say that again, Rick.” He said, “We’ve got a small stream of oil flowing into the booster pump house basement.” How can that be? We talked about it, and I said, “Well it’s got to be coming from upstream. It’s got to be a small leak in the buried pipeline.” I made sure Rick called OCC and I think we shut down the pipeline within the hour.

Brendan: I was actually off-shift in Fairbanks. It was a Saturday, and I was getting ready to go skiing, and I got a call from John Baldridge. He said, “We’ve got an incident going at Pump 1, we have a charter going up this afternoon, be prepared to be on it. And we’re starting meetings here this morning.”

Mike M: I was at Tozier Track on Tudor Road of all places – my daughter was doing a junior mushing race. My supervisor Dan Roberts gave me a call, and said we had a spill at Pump Station 1 and he needed me to come into the Operations Control Center (OCC). I was at the track with a truck full of dogs and a middle school daughter expecting to race. Because little was yet known about the nature of the event and because her start time was only minutes away, we let her race (she finished third!), and then we quickly loaded the dogs and sled, took everyone home, and then I headed for OCC.

Jerry: It was Saturday morning, and I was about to go to breakfast and got a call from the admin for the president, Reva (Paulsen). She said, “Get in the office.”

TAPS shut down just before 8:50 a.m. and Alyeska personnel launched into response mode.

JB: After five minutes of watching oil come in, we gathered in control room. The lead tech and supervisor let everyone know and recommended shutting the pipeline down. We can’t have oil continue to come in.

John: My next step was to go into work and do the callout to set up the Incident Management Team (IMT). Probably within 3 or 4 hours, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation joined me and the team there in Fairbanks, and the Environmental Protection Agency was there later that day.

Tom: John Baldridge had the IMT going in Fairbanks and we stood up a Crisis Management Team in Anchorage. I remember getting the question, “Do we really need to stand up a CMT?” Are you kidding me? The pipeline is shut down and it’s January! This is bad. Yes, we needed a CMT.

Brendan: I went in to the DIF in Fairbanks and sat in on the first meetings. Where was the spill, what were possible solutions? That was my baptism into that. Then I flew up that same afternoon to Pump 1 on a charter. I was a supervisor at Pump 1 at the time. My alternate Rick Larson was on shift, so I went right in as night shift supervisor.

Jerry: I went directly into the office and started pulling drawings on the booster pump area and the piping all around it to try to figure out where the oil could be coming from, and how to mitigate it. There wasn’t a lot of conversation; we all understood the urgency.

John: By early afternoon that first day, the Engineering and Projects teams had been informed and Mike Hale was nominated to go up there.

Mike H: (Jerry) Vega and I were told to fly up there and figure out what was going on. We started looking things over. We did some testing and determined where it was.

In addition to the spill, there were shared, growing concerns about how a prolonged winter shutdown could harm TAPS, including whether ice could form or wax could settle in the pipe, or whether a longer shutdown could even prevent a restart.

John: A lot of the early stuff fell on the OCC and the Oil Movements team and Betsy. The crisis was really, what do you do now that the pipeline is shut down and it’s 5 degrees above 0 in Prudhoe Bay and there’s a limited amount of methanol on the North Slope? We took producers to a 5 percent proration. That was difficult.

Mike M: My team mustered in the Operations Control Center conference room. We were watching temperatures and forecasting what the pipeline temperature would drop to. I was working with the rotating equipment engineer Jerry DeHaas on getting Pump Station 7 recycle heat going, which had never been done before. The coldest part of the line is typically between Pump 7 and 9. On night shift, we were doing calculations to see how much heat we could get out of the pumps.

Pretty quickly, key players defined the leak source at PS1.

Brendan: We had three booster pumps at the time and provisions for a fourth. The piping was there but the fourth was never connected. That’s where the leak was – where the pipe comes into the wall through the building.

Jerry: I would say it became obvious – it was coming between the pipe and the concrete. We knew we had a through-hole penetration somewhere in booster pump no. 4 dead leg. Because it was encased in concrete/slurry, we couldn’t just excavate and find where the leak was very easily.

With the leak identified, the next step was devising a solution.

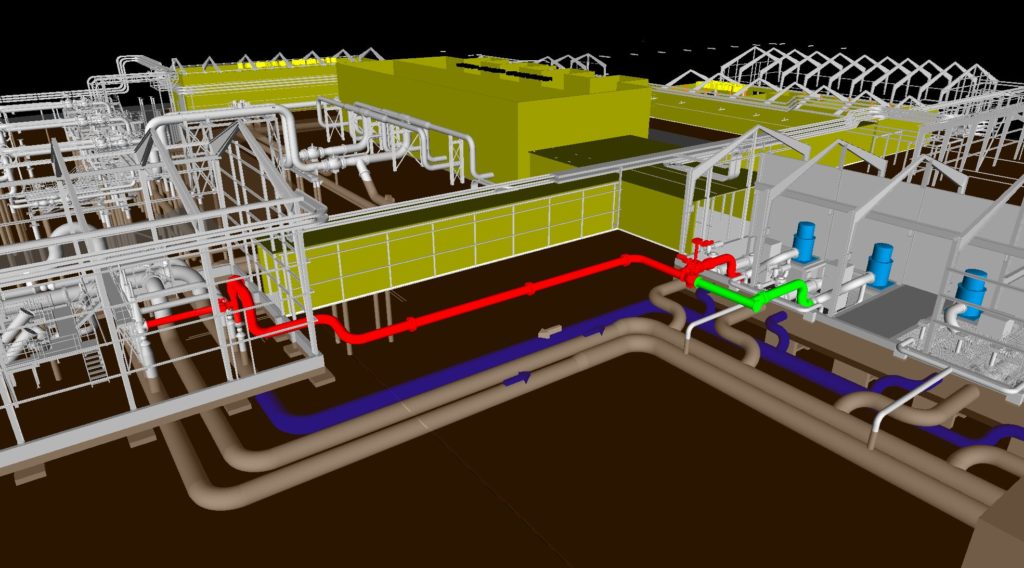

Brendan: I remember in that first meeting, they were like, “We could dig up the pipe and replace the pipe.” Well that wouldn’t work. We had several places on the pipeline where they put a slurry on the pipe – a lightweight concrete. There isn’t as much cement in the mix. It’s supposedly more structurally sound than regular backfill material. We didn’t know how hard it would be to get slurry off the pipe, not to mention if we have corrosion already, we’re not going there. So immediately, we knew we couldn’t do anything below ground, it had to be an above-ground pipe replacement.

Jerry: Shutting down the booster pumps was not an option. If you take the booster pumps out of the equation, you shut down the pipeline.

Mike M: The booster pumps are also required to pump oil from the Pump 1 storage tanks to the mainline pumps.

Mike H: You needed the booster pumps to help the mainline work; you had to have those going. There was a limited number of options really. And once you look at a drawing, well, the piping can only go so many directions. We realized the only way we could move oil was reroute from point A to point B and bypass the leak.

A solution took shape: teams would fabricate and install above-ground piping to bypass the leak site.

Mike H: We grabbed a tape measure and figured out: we could start here, run to here, tie into the suction relief line. We sent stuff to Jerry Albro back in Anchorage. He’d ask questions, we’d take new measurements.

Jerry: I was just trying to figure out the pipe routing – how could we bypass the effected section and then get it over to the main pumps? I’m trying to find materials that will fit, I’m calling the team at Pump 1 – how much space do we have between here and here to run a pipe through?

Mike H: Vega and I posed the case of where we had to start from and get to. We went from the booster pump directly to the relief line in the metering building, into the suction relief on metering. It was the quickest and shortest route. No one argued with it.

Jerry: You trust the drawings, but did somebody put something in that isn’t on the drawings? Mike Hale and Jerry Vega were my eyes up there and I was in the office just drawing up designs. Hale and Vega were the two. If I needed them, those were the two I called. The three of us had worked together for probably 20 years by then. If I was asking for something, they knew exactly what I was asking for and they would get me the right information.

Mike H: That’s what we were sent up there to do, was find a fix and make it happen. All of the other issues that were happening linewide – cold restart, the regulators – we were kind of shielded or protected from all that. Nobody got in our way.

Integral to the response success was securing parts and pieces needed to enable the work of welders and pipefitters in Fairbanks and Deadhorse.

Jerry: I recall leaving the office, I was about halfway home, and I got two calls. One was, they found a flange that I needed, and it was in New York. They asked, “How critical is it?” I said, I need it. They sent a single aircraft from New York with the flange on it, directly to Fairbanks. Then I got a call from a valve manufacturer in the Los Angeles area. It was probably 8 or 9 at night. They said, “We have the pieces and parts, but the valve isn’t assembled.” We said, “Assemble it and get it on an aircraft and get it to Deadhorse.” If the design required it, the company got it for us. Kudos to both Purchasing and Logistics. Purchasing went out and found the materials we needed. Logistics got them either to Deadhorse or to Fairbanks – wherever they needed to be. Their work was critical.

Brendan: Just about every day there was a chartered plane flying to Pump 1 with stuff. There was a box they made to catch crude where the leak was coming through the wall. They’d use a vac truck to suck the crude out of the box. One day the only thing on the plane was that box they built.

Jerry: The trust between Hale, Vega, the Fab Shop, the shop crew, and myself – we all trusted each other. And we all knew that if I asked for something, there’s a reason, get it. There was no back and forth or, “I don’t think it should it be this way.” Just get it done. Alan Beckett was my boss at that time and he pretty much said, “Go do it.”

Pipe rerouting wasn’t the only engineering work at hand: just north of Pump Station 8, a cleaning pig sat idle in the shutdown mainline.

Brendan: We had to get the pig out to take one risk out of the equation. It was north of Pump 8 at the time. To do that, they had to cut the mainline and put in two valves and put in this rollout spool. That was a pretty major undertaking in a few days.

Betsy: We didn’t want the pig to get frozen and we didn’t want the pig to push a bunch of stuff into the pump stations or Terminal when we restarted. You know who did the work on that? Jerry Albro.

Jerry: Back then, I was the contingency response piping engineer. My job was to have enough materials available and stored in Fairbanks to address any reasonable scenario or a problem and this was a problem. Pump 8 had already been straight-piped through so I started figuring out a design for routing piping and getting the pig spool in. It was not pre-planned at all. We started from scratch.

Mike M: We were very concerned about the pig pushing a big plug of ice into Pump Station 9 and shutting Pump Station 9 down. So Jerry Albro was multitasking between getting Pump 1 fixed and also designing the bypass at Pump 8 so we could restart the pipeline, catch the pig, and roll the pig out of the pipeline.

With engineering underway, Alyeska leadership worked with regulators to get buy-in on a response plan.

Tom: The strategy fundamentally was get everything going and overreact, because things can go south pretty quickly. We were pushing hard for a very aggressive response. Part of my job and the Crisis Management Team’s role was to create space so the people doing the work could do their jobs. The owners were supportive and part of the way to get and keep that support was to keep them informed as we went along, and it worked. We were proactive and I didn’t get any steering from them.

Jerry: At one point in the first couple days, I poked my head into a briefing at Anchorage headquarters. People were telling Tom Barrett how long it would take to do the bypass pipe. The numbers they were offering were very optimistic. I had a calendar constantly running in my head. I was thinking about what we were trying to design and build, how many parts were in Fairbanks, what was in Los Angeles or New York, how long would it take to get to Pump Station 1, how long it would take to weld and get hydro tested. So Tom looked over at me and asked me what I thought. I said, “It’s going to take longer.”

Mike M: There was a real tension with the regulators about restarting the pipeline. Operations and Operations Engineering recognized the longer we were shut down, the colder the oil was getting, the closer we were getting to seeing what happens when oil goes below the freeze point of water that’s in the oil. That’s something we just really didn’t want to learn in real time in the pipeline because the downside is so high.

On the North Slope, with limited inventory space at Pump Station 1, producers were scaled back to 5 percent production and pumping methanol into wells to avoid freeze-up.

Mike M: We had to get the pipeline running because if we didn’t, the North Slope was going to be in a world of hurt, and when you shut in wells they don’t always come back at the same flow rate. It has to do with the momentum of the oil. If you can’t keep a warm flow coming up through that 2,000 feet of permafrost, you can start freezing your wells with ice plugs. Also, the North Pole and Valdez refineries needed fresh oil to keep the refineries online or they would also be faced with a cold weather shutdown.

Betsy: The North Slope did everything to keep their lines safe. There was stress on our lab to understand, if the producers had to put methanol in, what would happen to the crude oil, how would we segregate it, how would we test it? We were sampling that, I remember – inputting it into a data base, trying to track that information down. In Oil Movements, there was stress every day. What were the tank levels? What are the producers doing? What’s their situation? It was very stressful.

John: I think there was just a lot of tension, simply because we knew what the stakes were. If the pipeline was shut down in the summer for a week, that wouldn’t be good from an economic standpoint. But the stress everybody felt was the fact we needed to get the pipeline back up and running. We needed to make the repair or else the entire North Slope was in jeopardy. But it became readily apparent that the bigger risk was not the leak at Pump 1, the bigger risk was to the entire pipeline system due to cold temperatures and very low flow. So the biggest challenge became convincing the regulators of this.

A KYP to employees late Jan. 8 said, “Alyeska employees and State and Federal officials are responding jointly to the incident. Engineers are assessing the situation and developing a plan to safely restart the pipeline.” Responders shared a growing understanding that a prolonged shutdown presented the largest risk.

John: When you’re doing your oil spill response training, it gets beat into your head, the first thing you do is control the source, then restoration. Usually that means you stay shut down. This was a first and probably the only time where we were convincing everybody that the best thing to do was to restart.

Mike H: We eliminated any potential exposure like a spark, and we put a box around the leak and put a vac truck in it to recover the oil. So I think from a practical standpoint, it wasn’t risky. Sure, from a regulator standpoint, they say, “What do you mean we’re going to start up with a leak?” But we were confident. We were containing everything and managing the leak so it wasn’t harming the environment, it wasn’t causing harm to the station.

Mike M: I knew the solution was to get the line started and figure out the political stuff later.

Tom: They thought they could get the pipe, the supplies, the crews, and get the bypass done in four days, maybe five if we had trouble. On the operations side, they were saying, “We’re going to have the Slope in really bad shape by then, and we’re going to be in bad shape by then.” So we knew we had to do a restart to keep the flow going and get the heat up and do another shutdown when the bypass was ready. We said, “Ok, let’s do it.”

Still, operating TAPS with an active leak was an unusual move that surprised many.

John: That was the first time we had an active leak, and we said we’re going to restart, and a lot of eyebrows got raised. I think even the EPA administrator was on the phone convincing some of his peers that it was the right thing to do.

Betsy: We were taking direction from the IMT, and the regulators were working with the IMT on what we were approved to do. It’s winter, it’s cold. Cold restart and low flow didn’t have the luxury of the data we have now. We didn’t know what was going on in the pipe. We were scared to death to stay shut down because we didn’t know what was going to happen, and above anything else we wanted to be able to restart.

John: The regulators we worked with most frequently understood the situation. The Unified Command was really strong and it really points out how those drills and exercises are beneficial when you have a crisis. You know the players on the regulatory side, and I can say there were incidents we had when regulators were difficult to work with and in this case, they weren’t. They were very supportive and the ultimately said the greatest risk here is to the pipeline, we need to get the pipeline running again.

Knowing crews needed time to prepare the bypass piping for installation, Alyeska needed official buy-in on a pipeline restart, despite the active leak.

Betsy: Because we couldn’t isolate the booster pumps and we were not going to be able to repair the leak before restart, we knew we needed time to do the bypass, and we needed heat in the line. Tom’s relationship with regulators allowed us to restart and operate, because the leak was understood – we just needed time. And Tom Barrett worked his magic.

Brendan: I remember Tom Barrett said he was going to start the pipeline and everybody freaked out – “You’re going to start the pipeline with a leaking pipe?” He talked them through it.

Mike M: Tom Barrett, he was with the company 2 weeks or less? Coming out of PHMSA, he understood the regulatory mindset. He might have been the best possible CEO for that situation. Getting the regulators to agree with Alyeska’s request to get the pipeline up and running was very important. The producers were hurting worse than we were. We were just sitting there with a pipe getting colder. They were freeze-protecting wells, going through methanol like it was going out of style.

Tom: We have this briefing, and one regulator says, “You’re really taking a big risk here.” And I just unloaded. I understand risk management, and I said, “Let me tell you what the real risk is here.” I went off, I talked about the pipeline, the pig in the line, the risks to the North Slope, production. I said, “This is a contained leak inside a building. This is on our property.” We had a smart approach and it was an appropriate balance of risk. We were well positioned to manage that startup. I was proud in those circumstances we were able to do a startup with an active leak.

On Jan. 11, federal and state authorities approved Alyeska’s plan to “resume limited pipeline flow under close monitoring pending the installation of the bypass pipeline,” according to a KYP to employees. TAPS restarted at 10 p.m. that evening. The initial shutdown that began Jan. 8 had lasted for 85 hours and 10 minutes, the second-longest shutdown in TAPS history.

Mike M: Betsy was shuttling back and forth between the Operations Control Center and the Incident Management Team and Crisis Management Team. I would come in for turnover in the evening, and ask, “Are we going to start tonight?” Her answer was “no” for several consecutive days. With each passing day, there was increasing tension among those of us who understood that not only TAPS, but the entire North Slope infrastructure was at risk.

Betsy: I remember being in the OCC. (Vice President) Mike Joynor said, “Go home, get some rest.” I said, “I can’t, I need to be here when things restart,” and he said, “No, go home.” That man doesn’t sleep. But I did go home and it was the wee hours of the morning when we finally got permission to restart. The stress then was, okay, we got permission, now what are the temperatures looking like? Is their ice in there? How’s the system operating? We were on pins and needles as we followed the coldest point all the way down the line to the Terminal.

With bypass piping ready for installation, the pipeline shut down again shortly after 12 a.m. on Saturday, Jan. 15.

Brendan: The main focus at Pump 1 was getting the repair piping in place, getting everything reestablished. That was really the focus.

Mike H: We took measurements, they had the piping there, they set up a couple welders and started putting it together, and we had it held up on temporary wood timbers. We cut a hole in the wall and were able to go from point A to B and bypass around the leak. It was pretty cool. We file fit there, right in place.

In a KYP to employees published Jan. 15, Tom said, “We have a significant amount of resources, tools and personnel on site at Pump Station 1 responding to this event. Our goal is to engineer and implement a solution so that we can safely return the pipeline to service as quickly as possible.” As the work progressed, there was a growing sense of admiration and relief, especially for the hands-on work in Fairbanks and the team on the ground at Pump 1.

John: Probably it was midway through that second shutdown, the piping was all coming together a little faster than they’d projected, and I thought, “OK, we’ve just about got it here. We’ve just got to get everything bolted up and get some oil in there.” There’s always a little trepidation. You worry about flow and vibration. Will there be undo vibrations on the pump? But everything worked. Our engineers did a phenomenal job on the fly. It was a great response.

Jerry: The Fairbanks Fab Shop gets the gold star. They did over 100 welds in probably four or five days, 24 hours a day, without any rejections. I’d give them the drawings. They’d cut, weld, x-ray, hydro test the pipe and prep it for flights to Deadhorse. If it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t have done it. There aren’t many guys left up there that worked on it, but they did good. In fact, I remember a BP executive who asked, “How many rejections did you have, and I said, “We didn’t have any.” He couldn’t believe it.

Betsy: I know Jerry Albro really well, and the shop in Fairbanks – Greg Campbell, Bruce Laiti, Kurt Helms – those guys know our line so well and they’re so good. I don’t know if we could have done it without that team because that’s a group that was working on this line before I got here, which was 1990. It’s their expertise with piping and welding and fitting and knowing our station that we were able to design it and fab it and get it up there and build it and have it fit. That in itself is a wonder. The work they did is amazing.

John: We wouldn’t have been able to respond the way we did without Houston and our contractors. The knowledge they had is sometimes even greater than our own people’s.

Tom: It was very tough conditions up there and our baseline contractors were excellent. The laborers, the equipment operators, the electricians, the welders – it’s tough gritty dangerous work. Doing a repair is one thing. Doing it in 10 or 20 below and the wind’s blowing and you have isolation and hydrocarbon issues, they pulled it off. They did so many major welds and every one of them passed inspection the first time. That’s above and beyond and particularly amazing in those circumstances, to have that many welds flawless on first pass. They were perfect.

With the bypass piping complete, the pipeline restarted on Jan. 17, 2011 at 2:50 p.m.

Betsy: I remember the angst around restarting. Following temperatures at locations down the line. Tracking that religiously. Figuring out where front edges were, what temperatures were going down the line. That’s what comes back to me, is this anxiety and angst about keep the pipeline going. Mike Malvick might remember differently but it seemed to me operationally, we didn’t have any big surprises or hiccups.

Mike M: It was a nonevent, which was a good thing. We had the pig out of the pipeline. We restarted and we didn’t have any hiccups. We didn’t have any ice show up. We came very close to freezing, to beginning to make ice. We were so lucky that the weather was unseasonably warm the entire length of the pipe. Based on the temperature data we had, we weren’t quite cold enough to make ice. But the thing is, you don’t really know where your coldest spot was. To do that you need to have an infinite number of sensors along the line. Instead, we had people in the field checking the pipe temperature under the insulation in between online temperature instruments.

John: We’d used all the methanol. There was no more to be found. All the methanol in the state got used. When we did that second shutdown to do the bypass piping, if that piping configuration hadn’t worked and we’d had to do a third shutdown, there would have been some major damage to the wells because they’d used the methanol. A third shutdown would have been disastrous.

The two shutdowns during the PS1 2011 event combined for 147 hours and 59 minutes, the longest in TAPS history.

Brendan: You feel it. It’s the old TAPS pride. You want to have things operating 100 percent. The earthquake back in 2002, that was my first shift at Pump 1 and the pipeline shut down, they shut the producers down. Everyone was scrambling. Same thing in 2011: you’re thinking, we’ve got to get this thing going whatever it takes, and get this repaired as quickly as possible.

Betsy: We weren’t moving oil down the line. It was high anxiety because of the unknown of restarting the line. I think the team was doing everything in their power to understand where’s the greatest risk, what do we need to be thinking about if we restart? Everybody went into overdrive to try to understand what we needed to be prepared for and to help incident command understand how dire it was.

Those involved have unique memories about the energy and activities that stretched across the duration of the response.

JB: At Pump Station 1, we were bombarded with a whole bunch of folks – compliance folks, liaisons from agencies. It was tough for about four days.

Brendan: It was pretty crazy. Basically it was all hands on deck. Everybody was focused on this event. We had engineers up there from Fairbanks, Anchorage, Valdez. We had all the contractors we needed. Since you’re on the Slope, there’s a lot of support up there. The producers were cranked back to 5 percent proration so all their crews were doing freeze protection on the wells. During the days you had all the politics and the planning, and everything gets executed at night. That was how it worked; we got a lot done at night.

Cathy: It was absolute insanity just trying to get the whole environmental piece together. It really ramped up and we brought in contractors. We were doing soil gas sampling, air monitoring, scoping out and sticking around the whole perimeter. I thought, “Why would we see oil in the tundra? The oil is in a basement.” But that’s what Jim Lawler would do, every single day. He’d go out in snowshoes and stick the snow, at least to be able to say we looked and we see nothing.

Brendan: Jim Lawler said, “I know the government is going to ask sooner or later if we’ve done a survey to see if there was oil anywhere.” So he’d go out a couple times a day around the perimeter and do this surveying, hiking in his snowshoes.

So much happened during that 10-day period, and so much work was completed with such success.

Jerry: It felt a lot longer. You didn’t have time to double check everything – your dimensions, whatever else. You sent it to Fairbanks for the fab shop, they’d get a fab set up and bolted in. Normally that project would have been planned a year in advance.

Brendan: If you’re used to seeing projects get executed and it takes 2-3 years to get a project done, getting it done within a week timeframe was pretty amazing. With all the hands and everyone there, it was a pretty good effort.

Mike M: I remember people were commenting, “Look at what we got done in such short amount of time! Why can’t we do that all the time?” Well, we had our best energy focused on one thing – not like a typical project engineer load where they’re managing several projects. Of course you can get a lot done in a short amount of time when you have the skills and the focus.

For those involved in the response, many whom enjoyed long Alyeska careers or still work here, the PS1 2011 shutdown ranks high in their catalogue of memories.

Mike M: In my 30 years with the company, that episode was the closest we came to not getting the pipeline started and having ongoing severe issues. We came very close to that. And the weather was on our side. It was the longest shutdown we’ve ever had. On top of that, it was the dark of winter.

Betsy: The 2011 spill was probably the most challenging because of weather. I remember there was a sentiment of great confidence in that team, particularly from (Vice President) Mike Joynor. He was always reassuring us that, look, it’s bad that we’ve had a spill, but it’s contained, and we don’t want to get hurt. Nobody gets hurt. We’re working fast, it’s January, there are extra hazards, and we’re going to be extra careful. Everybody really focused on that. Every group had a task, and we were all charging the hill.

John: It would rank right up there with the most difficult responses, it really would. What strikes me looking back on it is the amazing amount of teamwork – within the company, outside the company, the regulators, just a huge amount of teamwork. And the other part was just the incredible innovation, day and night, the innovation they had to have on the fly. Within 10 days we had the pipeline normalized. It was just incredible.

Tom: It was a defining moment for the company, that we could manage something that complex under those extreme conditions. Getting that bypass in, getting the line running again, the work was truly remarkable. I remember when we restarted and had oil over Atigun Pass, and you could hear the team cheering as they watched the monitors. That’s teamwork. That’s TAPS Pride.

Author’s note: Interviews for this piece were conducted in April 2022. Alyeska thanks those who shared their memories:

- James “JB” Johnson retired from Alyeska and today is a contractor at pump stations.

- Cathy Girard is an Environmental Coordinator Supervisor.

- John Baldridge retired in 2017 as Senior Director of Pipeline Operations.

- Brendan Labelle-Hamer is the Central Area Maintenance Manager.

- Mike Malvick is a Senior Flow Assurance Engineer on the TAPS Optimization Team.

- Gerald “Jerry” Albro was a Senior Discipline Engineer Advisor upon retirement in 2014.

- Tom Barrett completed a 10-year term as Alyeska President in February 2020.

- Mike Hale was an Operations and Maintenance Advisor when he finished his career with Alyeska in 2020.

- Betsy Haines retired as Senior Vice President of Operations and Maintenance in 2021. Betsy returned to Alyeska in August 2022 to serve as Interim Alyeska President.