ALYESKA ENGINEERS STEP UP IN WAKE OF BIG QUAKE

Published in February 2019

When the big quake struck Nov. 30, 2018, most Alaskans suffered similar reactions – ranging from fear to anxiety to alarm for loved ones and property.

Alyeska structural engineers Brian Johnson and Sterling Strait felt some of those things too; but the two men’s thoughts also shifted quickly to the Trans Alaska Pipeline System.

Sterling, Alyeska’s Seismic Program Coordinator accountable for responding to earthquakes impacting TAPS, immediately called the Operations Control Center: “All I could hear were alarms in the background,” he said. Learning the epicenter was centered in Anchorage, he continued to coordinate with engineering and field crews throughout the day until TAPS restarted.

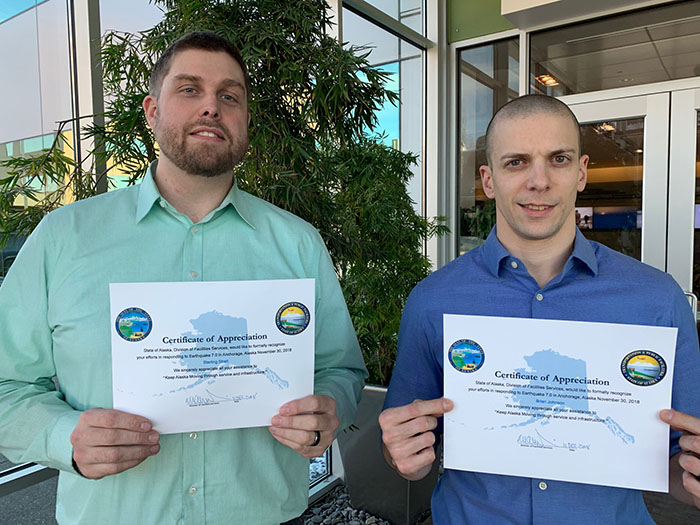

While the pipeline passed unscathed by the 7.0 tremblor that rattled Alaskans mentally and shook structures and roads apart physically, that wasn’t the end of work for Brian and Sterling. In the days following the quake, Alyeska freed up both engineers to assist the Alaska DOT inspecting and assessing state property for damages and usability. For their efforts in the aftermath of one of the area’s largest quakes on record, the two men were formally recognized with Certificates of Appreciation from the State of Alaska Division of Facility Services.

The appreciation was “a nice gesture,” Brian said. “But it’s not done with that in mind. It’s a community need, and if that’s your skill set, well, it’s your community.”

Added Sterling, “It’s a rare role for engineers to be able to help like that.”

Sterling and Brian are relatively new to Alyeska, but both have many years logged as structural engineers in Alaska’s oil and gas and construction industry. Sterling transitioned into the Seismic Program Coordinator role when the position opened. He knew as much about earthquakes as any good structural engineer in Alaska does. It’s part of working here, he said. You need to know how to design for earthquakes.

The day of the earthquake itself, both men were home – a flex day for Sterling, a sick day for Brian. When the shaking started, Brian instinctively grabbed his wife and newborn daughter and headed for what his engineer brain knew was the safest part of their Eagle River home, structurally.

In Anchorage, relaxing on his couch, Sterling said he realized the potential enormity of the quake “about five seconds in, when the shaking didn’t stop.”

After ensuring his wife and child’s safety, Brian said, “My second thought was about what was going on with the mainline and where was the earthquake in relation to that.”

Because that’s the thing seismically minded folks will explain, is it isn’t so much the magnitude as the location of the quake – in this case, the proximity to TAPS. The Denali Fault quake in 2002 was a 7.9 and struck directly beneath the pipeline, causing minor damage, shutting down the line for 66 hours and 33 minutes.

This one was much farther away, and after a precautionary shutdown and inspection, TAPS returned to operation that same day.

That didn’t mean the work was over for Brian and Sterling.

Sterling is involved with both the Structural Engineers Association of Alaska and the Alaska Seismic Hazard Safety Commission. He’s even coordinated training between the two organizations aimed at earthquake response. He reached out to colleagues and state officials, coordinated with his Alyeska supervisors, and within days of the quake, Sterling and Brian were on their way to survey state owned and leased infrastructure.

Remember in the days following the quake, how buildings were labeled with green, yellow and red labels? Green meant facilities were OK. Yellow signaled damages, but in limited areas. Red condemned buildings as dangerous for potential collapse and continued occupancy.

Working in teams, Sterling and Brian visited numerous facilities in the area, including storage warehouses and office buildings, assigning these colored labels.

Sterling even got to inspect the Goose Creek Correctional Center, where cracks snaked through concrete walls, alarming the confined inmates.

“It’s a concrete building, so there were cracks everywhere,” Sterling said. “We spent part of the time there doing structural engineering, and part of the time doing therapy and telling people, ‘It will be OK.’”

Brian agreed. While he found himself in some spaces that, to him, were clearly safe and unscathed, folks needed to hear that – and found particular solace hearing it from a professional.

“A lot of those folks, it meant a lot to them to see us walking around, looking at things closely,” Brian said. “It meant a lot to hear a structural engineer say, ‘There’s no sign of fatigue or overstress, there’s no sign of imminent collapse.’”

Just as TAPS withstood the Nov. 30 event, Sterling and others were validated to see seismic retrofit work at Alyeska’s Operations Control Center in Anchorage proved out, as the building weathered the quake.

The earthquake also proved an opportunity for Sterling to run through all Alyeska’s earthquake procedures and adjust where needed.