1991: Atigun Mainline Reroute Project

In 1988, Alyeska conducted an in-line inspection (ILI) of the pipeline. The results detected extensive pitting on numerous buried segments of TAPS, especially in river and floodplain areas, particularly in and around the Atigun River, where the inspection indicated extensive corrosion and advanced depth progression.

“This was very early in my career at Alyeska, but I remember it dominating conversations on the second floor of Bragaw for weeks as Engineering tried to get its arms around what this meant and what to do about it,” remembered Greg Kinney, an Alyeska site engineer who started in 1989.

Alyeska launched a program of confirmation digs in many of the areas where there were anomalies, and installed pressure containment sleeves when crews found heavy pitting. However, the pipeline in the Atigun floodplain was extensively corroded, and sleeving the 8.5-mile section of pipeline was not feasible or a cost-effective alternative. A project team was assembled in the fall of 1989 to design and engineer the Atigun mainline reroute project.

A significant project at a significant time.

The timing of the project coincided with activity related to the clean-up of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, an intensive corrosion investigation program on the entire pipeline system, and the immanency of the Gulf War. This project would be highly scrutinized by Alyeska management, regulators, and the general public.

In light of these circumstances, management set goals and objectives aimed at driving this project to a successful completion: No reportable spills of any magnitude through the duration of the project; No personal injuries that qualify as a lost time accident; Engineering work would result in a design that would last through the economic life of the pipeline; No unscheduled interruptions of throughput; and final cost of the project will not exceed the project budget.

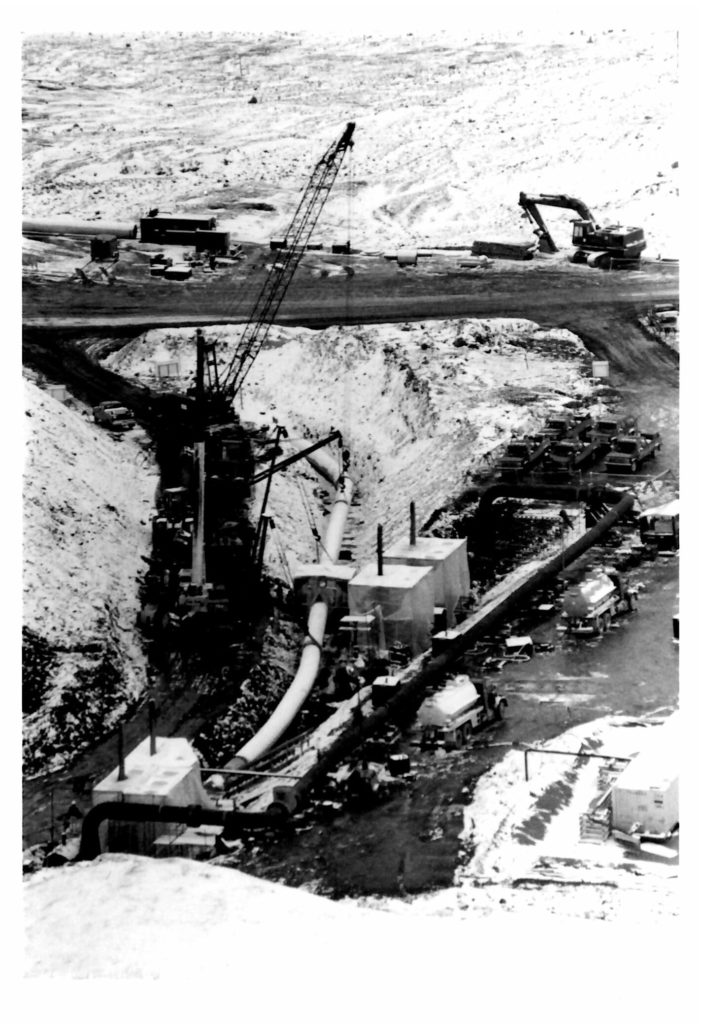

The scope of the project included replacing 8.5 miles of pipe in the Atigun floodplain, installation of three 48-inch valves, and the installation of a state-of-the art corrosion protection system. The new 48-inch pipe was coated with a fusion bonded epoxy, which was far more robust than the original Surfcoat coating and tape-wrap used on the original pipe. The cathodic protection system was enhanced with 4 anodes, one along each quadrant of the pipe.

The original pipe would be drained, flushed and cleaned, capped, and abandoned in place. Initially, the scope of the project called for a complete drain down of the segment into pump station storage tanks north of the construction site, followed by completing the tie-in of the new 8.5-mile pipe segment. However, this approach would have resulted in a two-day pipeline shutdown and a revenue deferment for nearly four million barrels of oil at a time when the average daily throughput was almost 1.9 million barrels a day.

Alyeska had been developing a pipeline stoppling system. The stoppling system involved installing a hot-tap on the mainline under maximum flow/pressure conditions and inserting a plug that internally seals and can withstand the full 1200 psi working pressure. Given the objective to avoid interruption of throughput, the project was redesigned to incorporate this emerging technology.

“At both ends, we had double stopple arrangements for the tie-in, plus a by-pass arrangement with a diesel driven pump that was used to reinject oil from the abandoned pipeline,” Kinney described.

Pat McDevitt, the retired Alyeska engineering coordinator for the project, expanded on project requirements.

“Due to the high pipeline pressure at the north end of the reroute and the high volume of oil, a special reinjection pump was required. It was diesel driven and had special safety ventilation features to separate the pump room from the diesel driver,” recalled McDevitt.

Because of the dangers of avalanches, rockslides, mudslides and slush flows to aboveground structures, the original pipeline in the Atigun River floodplain was buried. Burial depth averaged 15 feet to prevent damage from scouring caused by river flooding; scouring occurred up to depths of 10 feet in the area.

“The depth of burial in the floodplain was minimized by using a combination of gabion baskets filled with rocks over the top, plus a concrete matting system over the top of the baskets,” explained Kinney. “Together the system was configured to protect the pipeline from scour.”

The project required Alyeska to obtain 35 separate permits and design approvals from nine different regulatory agencies before construction of the pipeline could begin.

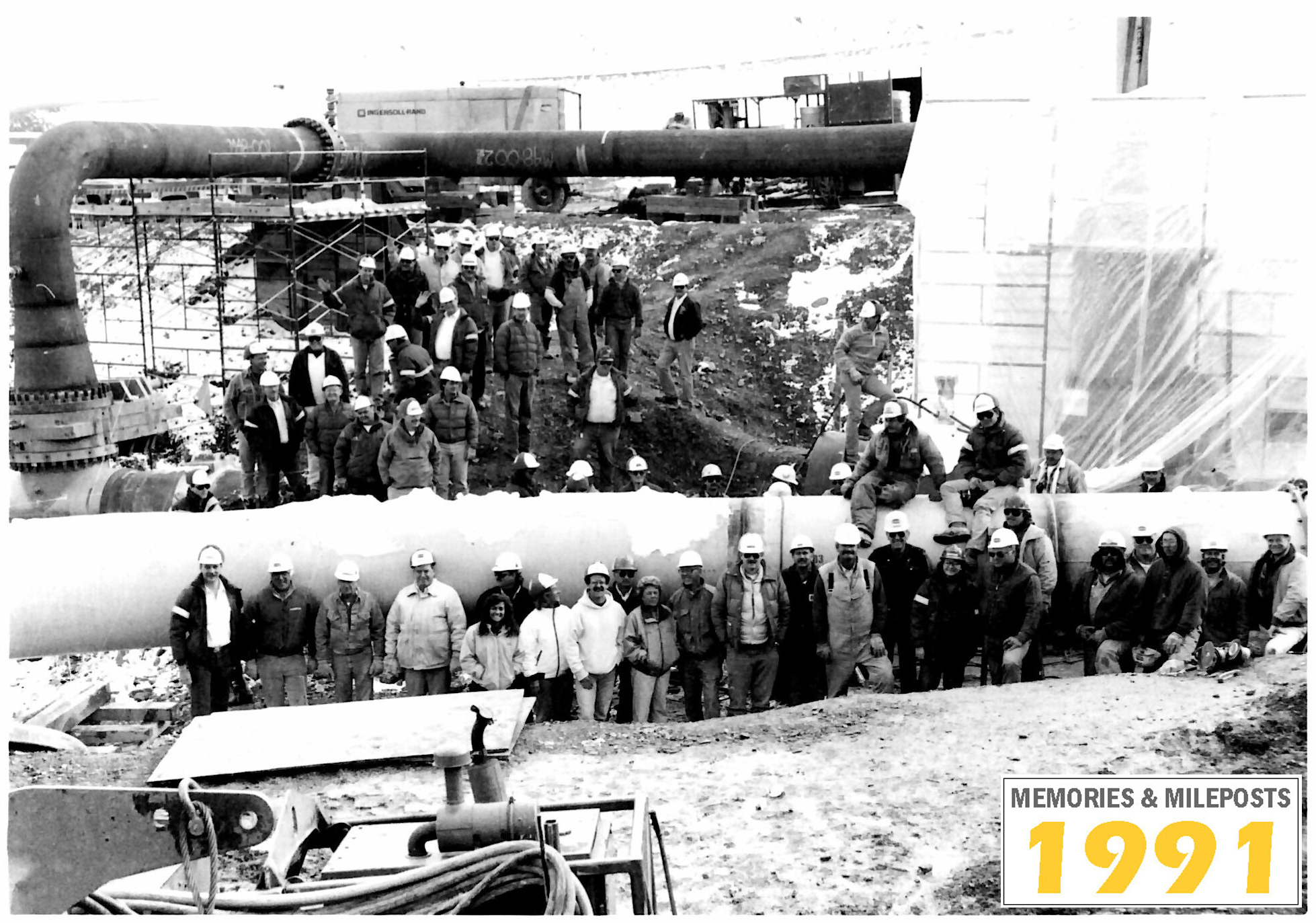

William Brothers Engineering Company (Tulsa, Oklahoma) was contracted for design engineering. HC Price/Northland J.V. (Anchorage, Alaska) was selected as the construction contractor and provided all the necessary services to complete the project including operation and maintenance of the camp and the construction equipment.

“HC Price had the pipeline section, Northland did the civil construction. MB Contracting was the sub-contractor that produced and manufactured all of the gabion rock for the gabion baskets… Dave Mathews was the senior project manager for HC Price. I was the General Foreman for the civil work. My main duties were ditch excavation, access right of way roads, etc… Tim Bridgeman was the Alyeska Construction Manager. My dad Calvin Bishop was the material superintendent for the company that produced the gabion rock. Tim and my dad had worked together 26 years earlier on construction of TAPS.” – Senator Click Bishop, General Foreman for HC Price on the Atigun Mainline Reroute Project

Battling weather, wildlife and water.

Environmental constraints played a major role in the development of the construction schedule. Seasonal considerations such as cold temperatures, frozen soils, available daylight – 3 to 4 hours during winter – avalanche dangers, and slush flows affected project timing. Fish habitat, raptor nesting areas, Dall sheep lambing season, caribou migration, bear habitat and tundra protection were also given primary considerations in establishing the schedule.

Environmental constraints played a major role in the development of the construction schedule. Seasonal considerations such as cold temperatures, frozen soils, available daylight – 3 to 4 hours during winter – avalanche dangers, and slush flows affected project timing. Fish habitat, raptor nesting areas, Dall sheep lambing season, caribou migration, bear habitat and tundra protection were also given primary considerations in establishing the schedule.

Mobilization, camp construction and right-of-way work commenced in the fall of 1990 to minimize wildlife disturbance and to take advantage of thawed soils and milder temperatures. Pipeline trenching, pipe laying and backfill operations were scheduled for completion during the first two quarters of 1991. This allowed ditching during the lowest water level conditions and minimized environmental disturbance to fish and wildlife.

Work in the canyon area of the project was completed first, with the new pipe backfilled prior to spring thaw and avoiding the risk of potential flooding in May. Despite these precautions, water management was still an issue.

“We did excavation in the winter. There is a tendency to think that if you are doing the excavation in the winter, you wouldn’t have any issue with water. That was not the case. The colder it is, the more water comes up in your ditch because the frost is pushing that water up. We ended up hiring two companies to drill de-watering wells along the right-of-way to try and keep the water table lower than the bottom of the ditch. The ditch was about 8 feet deep. The water was a big problem for us. We actually had to put more pumps in the ditch up near the Atigun river. We fought water all winter, it was a nightmare on the north end. The south end, going up the pass, it wasn’t as bad.” – Click Bishop

Of the two possible ditch construction methods, blasting was selected over conventional ditching in the narrow Atigun canyon area. The bedrock was shallow and the installation of the new pipe required excavation within bedrock. A relief trench was cut between the blast and the existing pipe. In many cases the blasting took place less than 30 feet from the existing operating pipe.

“We were drilling and shooting right next to the existing, operating, loaded line. It was pretty tight digging because we couldn’t risk damaging the loaded pipeline. … Price had a Vermeer trencher at Prudhoe Bay that I had run for them. So they brought it down from Prudhoe. It would dig a one foot wide, by 11-foot bottom of depth straight line along the working side of the pipeline. So now, you have a relief trench. When the shot went off, you had somewhere for the shot to go. With a straight line already cut, the hoe operator didn’t have to work so hard cutting and keeping that ditch line vertical up and down on the working side. It worked pretty well.” – Click Bishop

The southern portion of the project was located within an area of potential avalanche activity. The only road access to the project from the south was subject to periodic closure due to avalanche activity.

“Going up Atigun Pass in the spring, we had built the shoe-fly pass access road for the traveling public. We had to drill and shoot the main Dalton highway to get the pipe through there, then start up the pass. It was in the spring, we had this shot loaded and ready to go and for whatever reason, the State didn’t tell us that they were out there shooting avalanches with 105 howlitzer to bring the snow down. We were just getting ready to touch a shot off and the State starts shooting the howlizter and everyone froze. I thought our shot had gone off inadvertently and everyone kind of freaked out for a minute.” – Click Bishop

A successful project, on-time and within budget.

The project schedule spanned 27 months from conceptual engineering through commissioning in late 1991. An overall budget of $140 million was approved and the final project cost was $92.3 million. The most distinguishable cost savings decision was to competitively bid the construction as a fixed-price contract.

“In terms of benefits, this project was a smashing success,” said Kinney. “We have never had to go back and do another dig at the Atigun reroute section. It completely resolved the corrosion issues. There were numerous side benefits as well. Although this was not the first time we had done hot taps and stoppling, it greatly advanced our use. Although perhaps not a direct outcome, the requirements coming out of this project, and the discovery work that caused it to happen, led to advances in how we analyze anomalies.”

Thank you to Greg Kinney, Pat McDevitt, and Senator Click Bishop for contributing to this story.

READ MORE 45TH ANNIVERSARY THE EVOLUTION OF TAPS STORIES:

2007: Operations Control Center relocation

2013: With straight pipe installed, PS10 demobilization complete